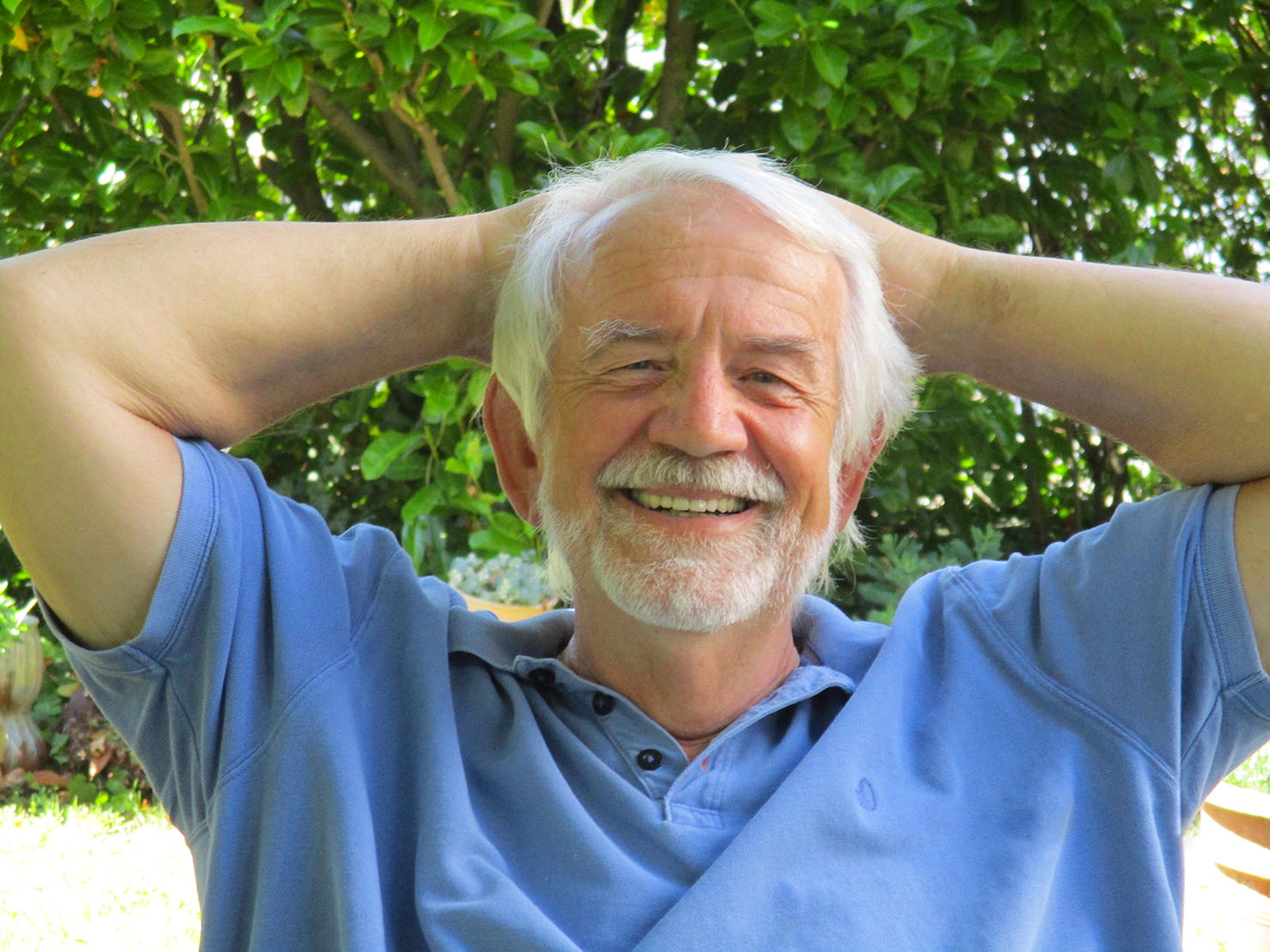

Bodo Röder

Bodo Röder – Widening Horizons. Article on German salt-glazer Bodo Röder, published in the international ceramics magazine Neue Keramik/New Ceramics in November/December 2022.

. . . . . . . . .

Widening Horizons

Bodo Röder, a venerable patrician of the wood-fired salt-glazing family, recently celebrated his 74th birthday. Looking back on a long and varied career, it is clear that the path he chose was not an easy one, especially considering his rather unorthodox beginnings. Having originally studied Russian and English at university, he turned to ceramics almost by chance. With limited opportunities towards the end of the seventies, he took up the invitation of an unpaid apprenticeship in a faience workshop in his late twenties, while at the same time teaching classical guitar to earn a living. It was, however, a difficult and creatively unproductive apprenticeship, compelling him to turn to other resources to help find an outlet to his artistic temperament. It would mean having to find his own voice by changing direction and moving away from earthenware.

By the nineteen eighties, he had returned to university to study fine arts and ceramics, qualified to become a teacher and had set up his own studio, initially in Darmstadt where he invested in a gas-fired kiln. He was particularly inspired by British potters, whose books he keenly devoured, and studiously explored the possibilities of reduction-fired stoneware and oriental glazes. Before long he had moved further south to a more rural location and, inspired by a recent article in a now defunct German magazine, set about building his own wood-fired Olsen kiln. It was a period of experimentation, trial and error and a heavy dose of perseverance, first with various glaze mixes, before ultimately settling on his chosen specialisation of wood-fired salt-glazing, a process deeply rooted in tradition. Since then he has dedicated his creative output to this medium.

Wood-fired salt-glazing is a demanding process and, as any salt-glazer would confirm, is renowned for its capricious nature, especially when aspiring to unearth its hidden secrets and attain those inherently lively surfaces it is capable of. And for Röder that was no different. With six firings a year, it meant that the intermediate periods of testing, calculating and experimenting with new glazing combinations and recipes were often arduous, protracted and full of uncertainties. However, when everything fell into place, the rewards more than made up for the effort involved.

Röder was also a keen student of the medium and was not averse to rooting out and adopting those processes that might facilitate workshop practicalities or specific techniques which would best suit his aesthetic expression: whether that was from articles and books or from the magnanimity of other salt-glazers, in particular those from Britain. He fondly recalls visiting Jane Hamlyn, for example, who opened his eyes to the subtleties and nuances of colour and showed him an innovative alternative to using wadding in the kiln. And Micki Schloessingk, who introduced him to mixing coarse household salt and moist sawdust to replicate the characteristics of natural sea salt, a technique he continues to abide by to this day.

In his search to find his own voice and artistic expression, Röder points out that pottery is the oldest craft known to humankind and that potters have always been influenced by other potters before them and by other cultures. They are therefore bound to a certain tradition. On the subject of major influences in his life, he unequivocally singles out Gerd Knäpper, the famous German potter who became a revered presence in Japan. Röder was particularly inspired by his carved and fluted forms, a technique that he himself would embrace and go on to master and develop. Ultimately, this would become Röder’s signature aesthetic: dynamic fluted spirals, organic textures and imagery, and naturalistic colours achieved through minerals and oxides, producing a depth to the salt glaze that cannot be achieved through traditional methods. Röder confesses that he has simply taken an old technique and developed new ways of interpreting it, free of gimmickry and artificiality. It is a credo he shares with his close friend and fellow salt-glazer John Dermer in Australia, an esteemed companion who often serves as the perfect sounding board for discussing ideas and aspirations.

When it comes to his chosen craft, Röder continues to speak with the enthusiasm and generosity of someone who gets genuine pleasure from sharing his knowledge and experience: he is a born teacher. Hardly surprising then that he was invited to take up various teaching and lecturing positions in ceramics, on subjects ranging from throwing, glaze calculation and surface treatment to kiln building and firing. Once again he points to his own experiences with British potters and their selflessness in passing on knowledge and advice that always left an indelible impression on him. He has nothing but praise for this open-heartedness and professional solidarity, and it is also the reason why he has always remained steadfast and determined to share his own secrets and motivate and inspire others to learn and find their own voice. His philosophy is simple: in order to improve pottery you need to widen horizons and inspire people.

Röder is not only an established presence at ceramic fairs, he has also exhibited regularly, most recently with a solo exhibition in the Terracotta Ceramics Museum of La Bisbal in Catalonia. He had the added honour of being the first non-Catalan ceramicist to do so. It was also the first time that wood-fired salt-glazed works had been exhibited in the wider area.

Looking back over his long career, Röder maintains that the life of a professional potter is a difficult one, predominantly devoid of those romantic sensibilities often associated with it, and one that requires having to accept extremely long hours, the labour-intensive nature of the work and the daily stresses that are part and parcel of its inherent unpredictability, especially as a wood-fired salt-glazer. That said, when everything falls into place, you are also energised and driven by the creative process. When it comes to ceramics in general and looking towards the future, it is a story with an open end. Having shared his knowledge and experience with so many younger people over the years, he hopes he has been able to inspire them to continue with a profession that is full of rewards, and with it, contentment.

Neale Williams

. . . . . . . . .

Bodo Röder was born in Zeitz, near Leipzig, in 1948. He studied at Göttingen University and fine arts and ceramics under Prof. Spemann at Frankfurt University. In addition to running his own studio since the early eighties, he has a long history of teaching and lecturing. A retrospective of his work was held in Dreieich/Frankfurt in 2018 and most recently he was invited to exhibit his wood-fired salt-glazing in the Terracotta Museu de Ceràmica de la Bisbal d’Empordà in Catalonia.